The African National Congress of South Africa marks 110 years of its existence on 8 January 2012. The Congress, which led the struggle for freedom and democracy in South Africa, has been governing the country since its independence in 1994.

Our Senior Contributing Editor Eric Singh**, who joined the ANC in 1951 and participated actively in the struggle against Apartheid, writes on 100 Years of Africa’s oldest and most enduring political organisation.

The Berlin-based veteran journalist focuses on the story of the passage of the Freedom Charter, a document that laid the foundation for the multiracial democratic South Africa, in Kliptown (now Soweto) on 25 and 26 June 1955; an event at which he was physically present.

——

Today, the people of South Africa are governed by a government led by the African National Congress (ANC). The path to this destination was long and hazardous, painful and bloody. It was full of sacrifices in which many of the best sons and daughters of the land paid with their lives to achieve this great freedom visualised by the founding fathers at the inauguration of the ANC 110 years ago.

That gathering in Bloemfontein – the Flower Fountain – on 8 January 1912, was an act of necessity and urgency.

Whites unite

After years of warring between the White peoples – English and Afrikaners (Boers) – which culminated in the triumph of British imperialism over the Afrikaners in the hard-fought Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902, the defeated Boers were forced into signing the Treaty of Vereeniging. This is a town in the then Transvaal (Gauteng Province since 1994), but the actual signing ceremony took place in Pretoria.

The treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, brought an end to all hostilities and the surrender of the Boers. They had to relinquish all their arms to the British, who in turn promised self-government to the Boers in Transvaal (the South African Republic) and the Orange Free State as colonies of the British Empire. The two Boer Republics then took cover under the sovereignty of the British Crown.

A few years after the passage of the Treaty of Vereeniging, the Union of South Africa was created on 31 May 1910. This Union gained relative independence (dominion status) under the 1926 Imperial Conference and the 1931 Statute of Westminster. That relationship remained until South Africa became a republic in 1961 and severed all ties with Great Britain.

Institutionalising Black oppression

The Black majority of South Africa was neither consulted nor invited to participate and air its views in the whole process leading to the formation of the Union of South Africa. Instead, no sooner had the White (English and Afrikaners) parliamentary machine got into action than one law after another was hatched out daily to the detriment of the majority of the people.

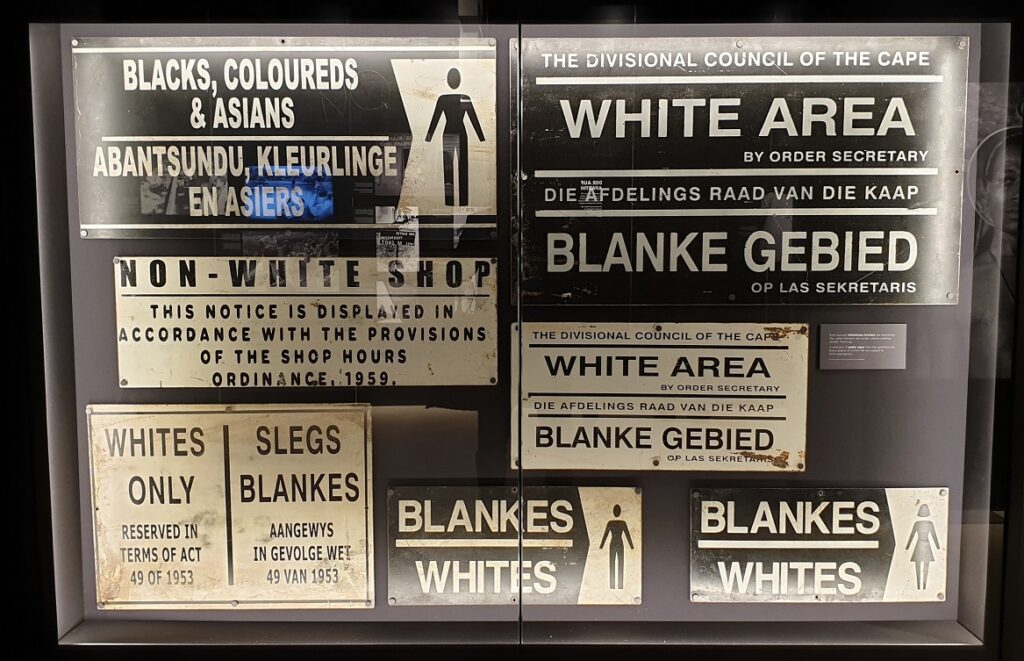

In effect, the laws rolling out of the all-White parliament had in essence one common factor – repression of the Black population in every conceivable situation. They were used to curtail freedom of movement; to deny Blacks from trading; to cripple their education; to deny the majority population its basic human rights and chances of equality; to deny the people of their right to economic development, cultural welfare and social advance. It was a downright racist parliament dishing out unjust racialist laws.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was the introduction of a draft bill in parliament in 1911, the so-called Natives Land Act (1). It was a law that allotted 90 per cent of the land to the minority White population and the rest, mostly barren and arid, 10 per cent to the Black population. In other words, the rulers did their utmost to stuff a whole whale into a sardine tin. There was therefore an urgency to oppose this draconian law. This was what led to the formation of what we know today as the ANC.

Blacks arise

What emerged from the meeting of Black representatives in Bloemfontein on 8 January 1912 was a two-tier South African Native Congress (changed to the African National Congress in 1923); the Upper House and the lower House.

Seven Paramount Chiefs were appointed as Honorary Presidents to constitute the Upper House. The National Executive (Lower House), under the leadership of the Rev John Dube as President, was elected to administer the organisation. It consisted of four ministers of religion, lawyers, an editor, a building contractor, a school teacher, an estate agent, an interpreter and a Native Labour Agent (a person who recruited workers for the mines). These were relatively young people who had received their education at mission schools and five of them had gone abroad and come back with degrees from British and American universities.

The composition of the Congress was moderate and very respectful. Their approach to problems facing the people was one of appeal and/or delegations to the various ministries, which in most cases ignored them.

Delegations were even sent to London to appeal to the British Government to bring respite to the majority of the people, who were reeling under the pressures of injustice brought to bear by the all-White parliament. Although these delegations were received courteously, they were politely told to go back home and solve the problem there because the British Government could not interfere in the sovereignty of the South African Government.

Enter Mandela, Sisulu, Tambo..

The whole face of the ANC took a new turn with the founding of the ANC Youth League in 1943 and the Women’s League in 1948. A revolutionary zest was introduced into the organisation that still believed in the capacity of the colonialists/imperialists for fairness.

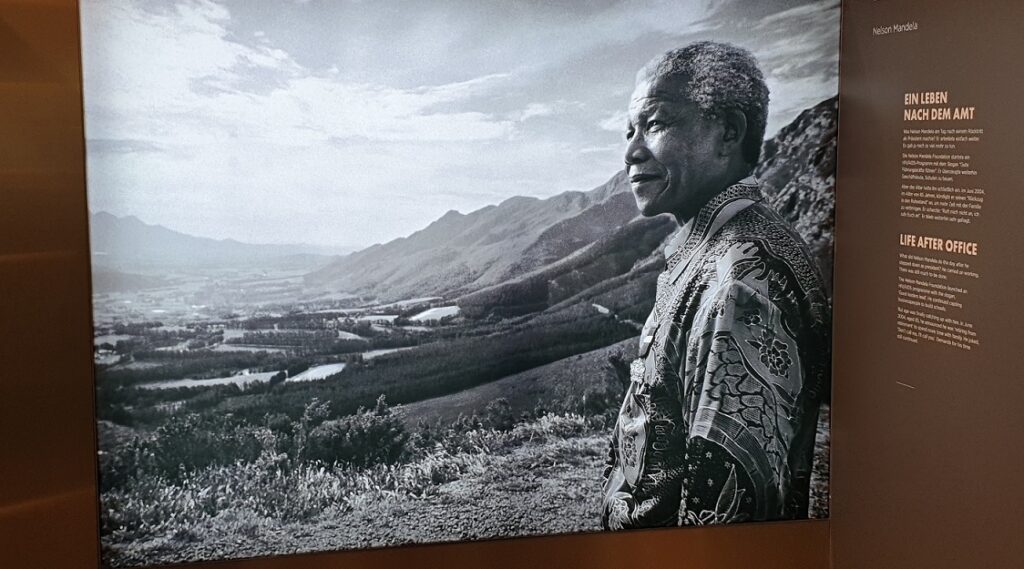

Led by such young revolutionaries as Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo, Nelson Mandela, Anton Lembede, Ida Mtwana, Lilian Ngoyi and many others, the youths pushed through the Programme of Action (POA) which was adopted by the ANC at its 38th National Conference in December 1949.

The POA had one message: universal franchise for all adults and the right to participate in all organs of the state. Gone were the days of cap-in-hand diplomacy. The fight was now being taken to the doors of the state. And the state was now in the hands of the National Party (Nats) whose members were all hard-core admirers of Hitler and members of the various Nazi groups that operated in South Africa.

The Nats, after defeating the pro-British United Party in the all-White general elections of May 1948, made no bones about their intent to tighten the screws of racist laws and, where none existed, new ones would be enacted. They did just that.

Apartheid increases oppression

With the coming of the Nats to power in 1948, the Black population began to feel the promises that the Nats had made to their followers over the years. Harsh laws, bordering on those which Hitler and his gang unleashed in Germany, were spewing out of parliament.

The ANC and its allies did not cow down to these barbaric acts. On the contrary, it met the offensive of the upholders of “law and order” with massive opposition. Of course, it was an uneven battle. The dice was heavily loaded on the side of the ruling class and the result was that there many casualties on our side.

Nonetheless, these actions brought a sense of responsibility and unity to the people and also drew attention overseas to the plight of the Black people in South Africa. It feels great to look back at those campaigns and the satisfaction of being personally involved in all of them between 1951 and 1965, when I was sent into exile. I can assure you, there were many. There was never a dull day. We had vowed not to give the fascist rulers of our country any respite.

Mass mobilisation against Apartheid

Nevertheless, in my belief, the most historic moment in the struggle was the adoption of the Freedom Charter in 1955 by the Congress of the People (COP). The COP, which has been described by historians as the most imaginative initiative of the ANC, was an all-encompassing alliance of those opposed to Apartheid from all races.

COP was the brainchild of Professor Z K Matthews***, a member of the National Executive Council of the ANC, and the decision to convene the multiracial forum was taken at the party’s annual conference in December 1953. No dates were however set.

Immediately this decision was taken, the wheels of the Congress went into action. COP Committees were set up in every town, district, factory, farm, etc. The idea was to involve a wide spectrum of people representing all sections of the social strata. Volunteers were recruited. Our job was to go from house to house and talk to the people. The mainstream media was not our friend. There were no computers or Twitter at that time. Not even TV.

For more than a year, COP was the key word. It was talked about wherever volunteers were occupied. After work, it meant visiting homes in our residential areas. It was a back-breaking undertaking. Fortunately, the people were most forthcoming. They spoke their minds, and left no doubt as to what they expected from such a document. Their main demands centred on bread-and-butter politics; better and free education; free movement; better health and medical facilities. And the right to vote.

Finally, in September 1954, it was announced that the COP would be held in Johannesburg on 25 and 26 June 1955. This announcement encouraged us to push ahead with our work. A few weeks before the great day, elections were held to nominate delegates. I was delighted to represent my residential area in Sydenham with 13 others. Now the job was to raise money for transport, and we finally raised enough cash to pay for a small van (covered) to Johannesburg. Unlike the highways of today, in those days a journey from Durban (Natal) to Johannesburg took a long time: 10-12 hours.

On reaching the border to the Transvaal (Gauteng) we ran into a roadblock. Those of us from the Indian community were not allowed to travel from one province to another (there were four in all) and had to produce passes to cross over. I did not have one and applications were a long, drawn-out affair. So I asked a friend to lend me his permit. It worked like magic. There was no problem crossing over, although there were consequences a few months later. In Johannesburg we reported at the ANC office and were told to make our way to Kliptown (Soweto).

The Freedom Charter

We did not believe our eyes when we finally reached the football ground where the conference was to be held. There was fun and frolic in the air. It was one huge sing-song. It was a real dance session. These were delegates who had arrived from all corners of the South African compass. It was gaudy and colourful. They were undaunted by the tough trip that they had to undertake.

It was made even more difficult by the police roadblocks that were set at vantage crossing points. Almost all of the Western Cape delegates were not allowed to continue their journey at the roadblocks and had no alternative but to return to their homes.

COP was attended by more than 3,000 delegates. Lots of hugs and back-slapping. We were almost complete strangers to each other. Some of the people I met at COP in 1955 have become lifelong friends. Quite a number of us are still alive.

Despite police interference, that weekend saw one of the most historic events that ever took place in the South African struggle for freedom and democracy. For two whole days, the delegates put forward proposals for a new, democratic, non-racist, non-sexist South Africa.

Finally, in the early evening of 26 June 1955, the Freedom Charter was adopted, chapter by chapter. It began with a preamble that reads:

We, the people of South Africa, declare for all in our country and the world to know that:

South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people.

The Freedom Charter is divided into 10 Sections:

- The People shall govern;

- All national groups shall have equal rights;

- The people shall share in the country’s wealth;

- The land shall be shared among those who work it;

- All shall be equal before the law;

- All shall enjoy equal human rights;

- There shall be work and security;

- The doors of learning and of culture shall be opened;

- There shall be houses, security and comfort;

- There shall be peace and security.

The Freedom Charter was a document that gave our movement a guideline as to what we needed and where to go and was the basis for the arrest and indictment of 156 leaders. They were charged with treason in 1956 and finally discharged in 1961.

I also had to go back to Johannesburg in October 1955 and was charged for “illegally” crossing the border with “false documents”. During the afternoon of the second day of the COP, the regime invaded our conference and surrounded the enclosed area. Nobody was allowed in or out.

It was announced that each and every person would be searched as the state believed that an act of treason was being planned by the gathering. They wanted to begin with their work immediately. “You wait until we have completed our work,” was the cry from the masses. Funnily, they waited. More than five hours. Then they searched us and confiscated documents and, in the process, they found the pass I was carrying. My friend in Durban was visited after a few weeks and he immediately spilled the beans which resulted in my trip back to Jo’burg in October.

“Not guilty on all counts,” declared the magistrate. What a sigh of relief. I was not happy at the prospect of spending the next few years in prison.

Struggle worth it

Today, I can say it was worth it. The fight was hard and fraught with danger but we dared to stick out our necks. It extracted a great deal of sacrifices from our people, especially our womenfolk, be she a mother, wife, sister, or however related. If they were not in the midst of the fray, then they kept our backs free. Alas! Many of our comrades did not live to see the dawn of freedom. Their contributions to the noble cause of freedom and democracy cannot be erased.

In 1979 the young freedom fighter Solomon Mahlangu marched to the gallows in Pretoria and uttered these brave words: “Let my blood water the tree of freedom”.

I am happy that I was an active participant and not a passive onlooker.

—————————-

**Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the print edition (December/January 2011/12) of The African Courier to commemorate a century of the ANC. The author, Eric Singh, died in Berlin on 11 February 2014 at the age of 82.

*Solomon Plaatje, who was elected General Secretary at the founding Congress, described the Land Act in his book Native Life in South Africa, published in 1916, thus: “Awakening on Friday morning, June 20, 1913, the South African native found himself not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth”.

**Prof Matthews was a lecturer at the Fort Hare University, the only institution catering for higher education for the Blacks. A number of Africa’s leaders studied there. Prof Matthews was later forced to resign because of his political activities. When the former British Protectorate of Bechuanaland attained its independence from Britain in 1966, Prof Matthews became its first Ambassador at the United Nations.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.