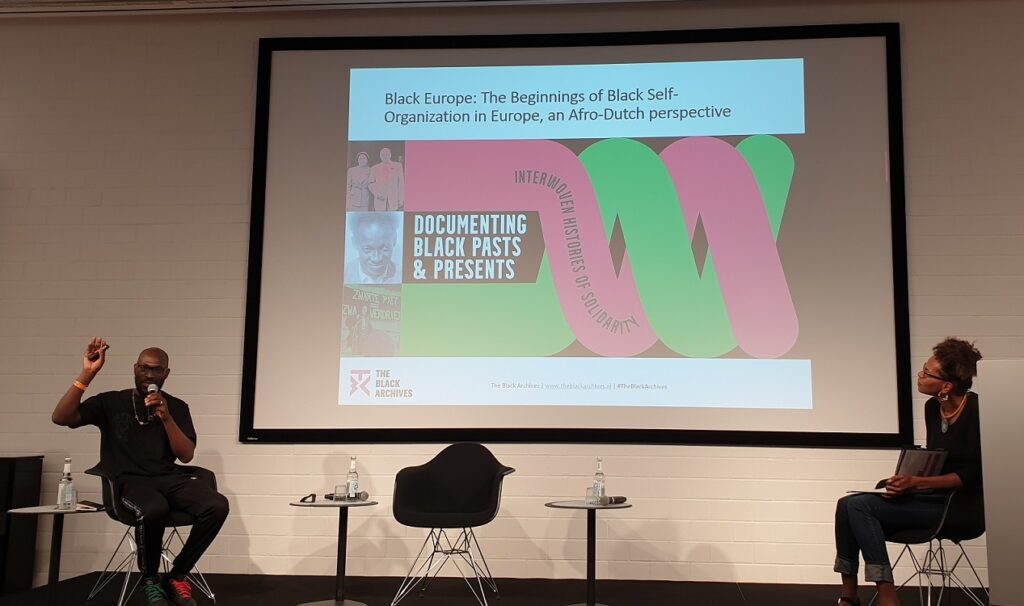

An international conference sponsored by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and the Initiative of Black People in Germany brings together activists and scholars in Berlin

By Femi Awoniyi*

People of African descent have historically been part of European societies. Indeed, their roots on the continent date back centuries, even if this fact is barely acknowledged in modern history books.

“Black Europe: The Beginnings of Black Self-Organization in Europe”, an international conference organised by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and the Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland (Initiative of Black People in Germany or ISD), brought activists and scholars from across the continent to Berlin on 10–12 June to dive deeper into this history and its relevance for Black communities today.

Over three days of presentations and moderated discussions, participants explored “what Black people have done to unite and collectively represent their interests under the adverse conditions they face in racist societies”.

Eight speakers discussed the recent history of Black self-organisation in their respective home countries in Europe. In addition, the influence of the Black movement in the United States on its counterparts in Europe was discussed by two scholars.

Kicking the conference off, Daniela Trochowski, executive director of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, said the conference was necessary to promote a counter-narrative to the popular impression of ethnic homogenous populations in Europe and deflate the myth of a lily-white continent.

Ms Trochowski said the foundation, which is affiliated to Germany’s socialist Left Party, hosted the conference because of its commitment to the unravelling of racist structures responsible for police violence, discrimination in housing and employment, and other structural disadvantages to which people of African descent are subjected.

The United Kingdom and France

The first presentations and subsequent panel discussions on the conference’s opening day were on France and the United Kingdom. Zahra Dalilah, a Black feminist writer and activist from London, pointed out that the documented history of Black self-organisation dates back to 1772.

She talked about groups formed in the 1920s, beginning with students from Africa and the Caribbean. These bodies birthed the pan-African and anti-colonial movements. An important moment in recent British Black history was in 1948, when Afro-Caribbean migrants began arriving in the UK and settling in big cities.

Facing widespread discrimination and resentment, it was only a matter of time that the Afro-Caribbean community began to resist, culminating in organised protests such as the bus boycotts of the early 1960s.

Black agitation since the 1970s has been directed against police violence and focused on social and economic rights, such as for decent housing, dignified jobs, and better working conditions, Dalilah said. New issues, such as the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the discrimination of Africans fleeing the war in Ukraine, have come to define the Black movements of today, she noted, adding that women and feminist groups have also become pronounced in the community.

The history of Black self-organising in France is similar to that of the UK, Yéra Dembele from the Fédération Euro-Africaine de Solidarité (FEASO) said in his presentation. Paris-based Dembele talked about the formation of Black trade unions and social initiatives beginning at the end of World War II. These eventually became active in the anti-colonial movement. Since the 1960s, self-organising has been geared towards fighting for better housing, wages, and working conditions as well as against discrimination, Dembele noted.

While Black people, estimated to number between 3 million and 5 million, constitute between 2.5 and 7.5 percent of the French population, they are not recognised as a group. France does not collect data on ethnicity and race and hence does not properly recognise communities of non-French ethnic origin.

Austria and Switzerland

The discussions on Austria and Switzerland followed the ones on France and the UK. Mandu dos Santos Pinto said the first community associations in Switzerland emerged only in the early 1980s, following the arrival of the first generation of Congolese refugees. Self-organisation, which started as national associations and provided the African migrants forums to socialise, has evolved over the years with the emergence of groups such as Sankofa that encompass all people of African descent and pursue issues of general concern such as racism and discrimination.

Simon Inou traced the beginning of the Black movement in Austria to the formation of African student associations about 60 years ago. Black people were not an issue in public discourse until Jörg Haider became leader of the right-populist Freedom Party (FPÖ) in 1986, after which the party began to stoke anti-immigration sentiment in the country.

The FPÖ depicted people with a migrant background as a danger to society, with Africans often stigmatised as drug dealers. The racist campaign pushed Black people onto the defensive, and they began to organise and resist. Black organisations in Austria have grown more diverse with the emergence of women and youth groups in the past two decades.

Poland and Germany

The conference’s third panel focused on the Black experience in Poland and Germany. Dr Tade Omotosho talked about the emerging Black community in Poland. He said there were about 5,400 Africans in the country, most of whom came to the country as students. In addition, there are naturalised Black citizens as well as a young generation of Polish-born Blacks. Although the community is young, recorded Black presence goes back many decades.

Omotosho said there were no records of strong self-organisation until recently. He singled out the Somalian Foundation, founded in 2007 as a forum of contact between Poles and Africans, as a centre of the organised Black community.

As small as the community is, it has recorded successes in Polish politics, as two Africans have been elected to the Polish national parliament at different times, Omotosho noted. This is an inspiration to the young generation, which has become more assertive, to participate in politics and society.

Karen Taylor narrated how Audre Lorde (1934–1992), a writer and activist of Afro-Caribbean and African-American descent who lived in West Berlin in the 1980s and early 1990s, helped ignite the Afro-German movement.

It was Lorde’s encounter with young Afro-German women, such as Katharina Oguntoye and May Ayim, that led to the landmark publication Farbe bekennen. Afro-deutsche Frauen auf den Spuren ihrer Geschichte (Showing Our Colours: Afro-German Women Speak Out).

The book, which describes how Germans of African descent were often made to feel foreign in their own country, led to the formation of the ISD, Afro-German Women (Adefra) and other Black groups. Farbe bekennen and the organisations it inspired established the Black German movement of today.

Taylor said the UN’s International Decade for People of African Descent has also brought many Black organisations together to engage politically beyond their community work. “The community wants to speak for itself and not merely be talked about. This increases the political visibility of the Black community”, she noted.

That visibility is paying off, as Black organisations are now consulted by governments on a broad range of issues, such as police-community relations, refugees, and education. In fact, some of the Black community’s demands, such as a reappraisal of Germany’s colonial history, were included in the current federal government’s coalition agreement, Taylor revealed.

Portugal and the Netherlands

The second day of the conference opened with a focus on the Black movements in Portugal and the Netherlands. Beatriz Gomes Dias, politician and anti-racist activist from Lisbon, pointed out that Black people were already very organised in the early twentieth century, founding newspapers, forming political groups, and being active in public life. In fact, there were two members of the Portuguese parliament at that time.

The early Black organisations were anti-colonial and supported the independence struggles in the African territories colonised by Portugal, Dias, a former member of the Portuguese parliament for the Left Bloc, said.

The challenges facing the Black community today include racial discrimination, poor housing and unemployment. The community demands equality, the criminalisation of racism and an end to police violence. Black people are also demanding a reappraisal of the country’s colonial history by recognising historical crimes against Africans.

Mitchell Esajas of The Black Archives, an initiative that documents the history of Black emancipation movements in the Netherlands, said there was already an association of Surinamese in the country in the 1910s. The issues of racism, discrimination and police violence are old and have always elicited Black resistance in the Netherlands. Contemporary Black movements demand, among others, an end to police violence and socio-economic deprivations manifested by a high unemployment rate and poverty in their community.

Black Atlantic – Black Europe

The second session of the second day of the conference, featuring Dr Marion Kraft and Prof Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson, was devoted to the influence of the Black movement in North America on its counterpart in Europe.

Marion Kraft, a Berlin-based Afro-German scholar and translator, pointed out that African-American cultural influence had been of great inspiration to Afro-European self-organisation and self-expression. She talked about Black musicians who toured and lived for some time in Germany in the 1920s. Kraft also reminded the audience of Audre Lorde’s role in the emergence of the Black movement in the mid-1980s.

Waldschmidt-Nelson, professor of transatlantic history and culture at the University of Augsburg, dwelled on the relationship between liberal German scholars, ministers, activists and African-American civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr in the 1960s.

The presentations and discussions show that the evolution of Black communities in Europe follows a similar trajectory. While nationality and ethno-cultural identity played a significant role in self-organisation in the past, the new generation of young Black people born and raised in Europe focuses on social issues such as discrimination, racism and the living conditions of deprived communities.

The conference not only looked backwards, but also forward. A workshop on the third day of the conference discussed what needs to be done in the future. Closer cooperation among Black communities through the sharing of information, knowledge and experiences was identified as key to a stronger Black Europe, just as archiving Black history is critical for self-education and self-empowerment. Participants also called for regular exchanges between the diaspora and African institutions.

One thing is clear: Black European self-organisation will benefit greatly from stronger connections between activists.

Femi Awoniyi is editor-in-chief of The African Courier

—-

This article is also published on the website of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, rosalux.de

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.