Lovers of African literature congregated in Berlin for the African Book Festival Berlin on 16 – 17 July 2021 to celebrate writing from the Continent and its Diaspora. The festival, first held in 2017, continues to go from strength to strength. Although this year’s event had a Lusophonic slant to it, celebrating, in the main, Literature and Music from Portugal, Brazil and Angola, there was still enough continental diversity on show. Our Contributing Editor, Michael Nnaji, covered the event and brings you this report.

———

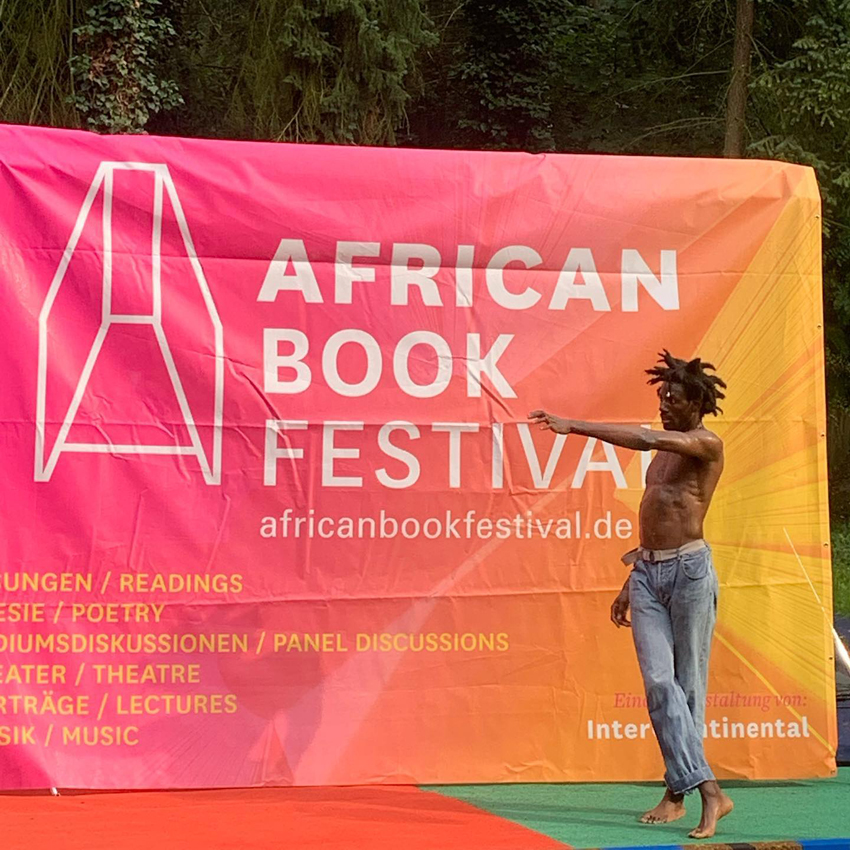

This year’s African Book Festival in Berlin took place in the lush green surroundings of the open-air ambience of the Freiluftkino in Rehberge, Berlin, which is only a stone’s throw from the Volkspark book-ended by the River Plötzensee.

Designed in the form of a roofless giant auditorium, it was the perfect place to wine and dine over the latest works from Africa and its Diaspora. The fact that the event is into its fifth year shows that the genre is not only gaining traction but also serves a niche that has been neglected for years. In many ways, it is a coming of Age of the second generation of immigrants from the continent.

Huge credit must go to the Interkontinental e.V., the NGO founded and run by the enterprising trio of Karla Kutzner, Stefanie Hirsbrunner and Venice Trommer.

The annual event which witnessed a pared-down version last year due to the Corona Pandemic was this year open to visitors in accordance with local health regulations.

Fine music and readings from Angola and Brazil and more..

This year’s event had its emphasis on Lusophone Africa and was aptly curated by the Angolan writer and musician Kalaf Epalanga who, in every sense, rose to the occasion, treating the audience to fine music and readings from Angola and Brazil.

Over the two days of the festival, there was a clutch of exciting discussion panels which centered, among others, on the perils of writing in troubled societies and the author and the concept of responsibility.

Unsurprisingly, migration and its discontents, as always, invariably tend to dominate such agendas. It remains one of the great quirks of literature that great art can only be engendered by suffering and not happiness.

Who wants to read about peace, joy and pancakes? Truly great art is however distinguished by the surprising and moving creativity and turns that it takes, a technique in which much of the top brass of the African and Diasporan literati excel.

The festival’s theme this year was billed “Telling the Origin Stories”, an allusion to a technique deployed in film production that deploys flashbacks to shed light on the motives of protagonists. In his program notes, Epalanga remarks that those who fail to tell their stories risk becoming invisible in the end. Or to borrow that aphorism of the history of hunting looking completely different if lions could write and tell their side of the story.

It was a truly befitting theme as writers, musicians and artists from all over the continent provided background information on the origins of their love for their trade. It also cataloged the existential struggles that authors on the continent and diaspora continue to face in their search for recognition and relevance in their various societies, places where little or no regard is given to the life of the (creative) mind.

Engineers and doctors instead of storytellers?

The Congolese author Fiston Mwanza Mujila recounted how he was once reproached by the powers-that-be for choosing to become a writer and told in no uncertain terms that the country needed engineers and doctors, and not idling, good-for-nothing storytellers.

A rapt audience was also treated to the inner workings of the mind of the Afrodiasporan writer as they grapple with their dual and sometimes multifarious heritages in self-imposed exile.

Mujila for instance likened writing to tending to a garden, or better still, vineyard. A place where, if you will, labour intersects with love. He cites various European influences, ranging from Thomas Mann, Siegfried Lenz to Günther Grass and how he endeavours to bring his own native Congolese influences to bear.

The Ghanian-Nigerian writer Bisi Adjapon revealed how she was inspired to write by Ghanaian fairy tales, a process that started innocuously as a schoolgirl but has blossomed over the years culminating in her nomination for the prestigious Caine prize.

The Eritrean writer Sulaiman Addonia mused about the loss that political, religious, ideological and philosophical restrictions impose on us, preventing us from reaching our full potential. He longingly envisages an alternative universe where this potential would be fully attained, making the world a richer more diverse place.

It was very much in keeping to spirit of the occasion, that spirit of inclusivity that harkens to the words of Chairman Mao in “letting a thousand flowers bloom”.

In many ways, events like the African Book Festival help to break down real and imagined barriers and open new frontiers in the interaction and dialogues between cultures.

Tellingly, art offers unparalleled avenues for exploring the human psyche and giving birth to New Realities, the engine of evolution that is crucial to our survival as a specie.

In the end, it is tempting to envision a win-win situation for both parties; host countries providing the infrastructure while the migrants offer fresh perspectives, new and creative ways of seeing things. Like in the parable of the blind men and the elephant, the world can indeed be a very complex place to make full sense of.

Can Literature and Art change the world?

Adaonnia would eventually give his take on whether a writer’s work can change the world (for the better). He referenced an older author who realised much later in life that, it was he, the writer that had undergone transformation. In other words, large scale visible changes can obviously not be brought about by art. If anything, change in that sense can only be by accretion.

This was the question panelists grappled with severally. In the end, there proved to be no easy answers. One panelist begged to differ, however, recounting the tale of a woman in Argentina who fell in love with the works of the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie and subsequently applied for and got a job at the Nigerian Embassy in Buenos Aires. She ended up marrying a Nigerian and adopting a Nigerian child. All this came about because she read the works of fiction by a talented writer!

There were not only established writers at the event but also up and coming ones, determined to make their mark in the field, a fact that indeed bodes well for the future of Afrodiasporan literature.

Beyond the literary and musical offering, there were performances by the Congolese dancer Exoce Kasongo who kept the audience spellbound with his improvisation onstage – along with his sidekick Epalanga – set to music and poetry.

The Interkontinental Bookstore also set up shop, displaying an impressive collection of books. Food, fabric, art children’s book stands were also on hand to complete the African experience.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.