Angolans vote Wednesday in an election that will see President Jose Eduardo dos Santos quit after nearly four decades in power, but with his hand-picked successor widely expected to take over.

The long-time leader has laid the groundwork for his designated successor in an oil-rich country where poverty, corruption and human rights concerns are unlikely to dissipate anytime soon.

Defense Minister Joao Lourenco is the ruling MPLA party’s candidate to succeed dos Santos, who is expected to remain party leader. Lourenco, whose association with 74-year-old dos Santos dates to the war against Portuguese colonial rule, has pledged to fight graft if elected.

He would likely encounter the entrenched interests of an elite partly dominated by the president’s family, including daughter Isabel dos Santos, who heads the state oil company Sonangol although media reports have indicated that she could vacate the post.

Isabel dos Santos is reputed to be Africa’s richest woman, hailing from a nation with one of the highest poverty rates in the world. Angola endured decades of civil war that ended in 2002, leaving at least half a million people dead, several million displaced from their homes and infrastructure devastated.

Despite evidence of cronyism, the selection of Lourenco as a successor to dos Santos and the avoidance of a “dynastic transition” to one of the president’s children indicates “that internal checks and balances may be stronger than many believed,” said Soren Kirk Jensen, an associate fellow in the African program of Chatham House, a London-based institute.

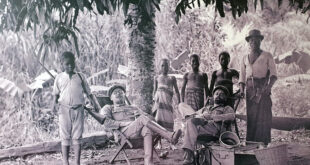

“As the process unfolds, it is clear that Angola is following the pattern of gradual democratization from other governments in Southern Africa headed by former liberation parties that led the armed struggle for independence from colonial powers,” Jensen wrote in an analysis.

The MPLA, whose Portuguese acronym means Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, is the election front-runner after winning in 2012 with 72 per cent of votes amid allegations of irregularities.

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) party, a former rebel force that fought the MPLA in the civil war, is the main opposition challenger and won nearly 19 per cent in the election five years ago.

Heavily reliant on oil production, Angola has since struggled because of the global fall in commodity prices and the opposition seeks to capitalize on what it says is growing discontent in the southern African nation’s young population.

About 9.3 million Angolans are registered to vote for the 220-member National Assembly, and the winning party will then select the president. Dos Santos, who has received medical treatment in Spain this year, appeared alongside Lourenco at a weekend rally on the outskirts of the Angolan capital of Luanda.

“I come here just to reiterate my personal support to our candidate,” said dos Santos, according to the Portuguese news agency Lusa. “I do not doubt that the MPLA will win the elections, and he, our candidate, will be elected the next president of the republic of Angola.”

Lourenco, in turn, praised the president, describing him as “the captain of the team” and saying “he has always been in command.”

Dos Santos, who is praised by some Angolans for his role in ending the civil war, has previously indicated that he was considering retirement and then remained at the country’s helm, though this time it appears certain that he will relinquish the post of president.

The only other African leader who has ruled longer – by about a month – is President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, 75, of Equatorial Guinea. Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe, 93, has been in power since independence from white minority rule in 1980.

Angolan critics have alleged that the ruling party has unfairly used state machinery ahead of the election, noting that most campaign coverage on radio and television stations has focused on the campaign of the MPLA.

Election observers from other African countries will monitor the vote, but the European Union is only sending a small team instead of a full-fledged observer mission because it says the Angolan government wanted to impose restrictions, including limited access to polling stations around the country.

In a statement, Amnesty International said Angola’s next leader must work to reverse attacks on freedom of expression and other rights. Criticizing the president is considered a crime against state security in Angola, and peaceful protesters, journalists and others have been jailed for long periods or “forcibly disappeared without a trace,” the group said.

AP

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.