The founder of Afrobeat died on 2 August 1997. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of his death, The African Courier remembers Fela Anikulapo-Kuti – musician, crusader for social, economic and political justice, and Black emancipation. Our contributing editor, Robert Ajani*, discusses the life of the legend.

—————————————-

The making of Fela

Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, musician, Africanist, humanist and politician, was born on 15 October 1938 into an elite Christian family in Abeokuta, western Nigeria. His late brothers, Prof Koye Ransome-Kuti and Dr Beko Ransome-Kuti, both medical doctors, left their imprint on public service in Nigeria. Koye was once Nigeria’s health minister while Beko was an accomplished political activist. Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka is their cousin.

Fela left for England in 1959 to study music at the prestigious Trinity College of Music, Oxford. He returned to Nigeria in 1963 and formed his first band (with JK Braimah), Koola Lobitos in 1965.

His mother, Mrs Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a friend of Kwame Nkrumah, was a political activist and dogged fighter for women’s rights. She was also a staunch member of a political party led by Nigeria’s first post-independent leader, Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe, and played an active role in the struggle for the country’s independence from British colonial rule. But Mrs Ransome-Kuti was never rewarded with a political office.

Whether this ill-treatment of his mother rubbed off on Fela in his later career and struggle remains speculative. Fela agreed, in an interview, that his mother influenced him politically, but his chosen course in life had nothing to do with his parents. Incontrovertible, however, is the fact that his band’s tour of the United States of America in 1968 was a turning point in his subsequent transformation.

Indeed, it was his meeting with an African-American woman Sandra Izsadore, a member of Malcolm X’s Movement, on his American trip that opened his eyes to the struggle of the oppressed Black people. “Sandra talked me out of stupidity,” Fela would later say of the woman.

Fela got introduced to the Black power politics of Malcolm X and Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism. In short, Fela became schooled in African political education. The end-product of that trip is his song Jeun koku (Yoruba for eat and die – against the sit-tight African political elite). The new song is a combination of Western music education and ‘African-polyrhythm and physicality’, the Afrobeat.

Fela then changed his name from Ransome-Kuti to Anikulapo-Kuti (in rejection of Ransome as a colonial name), and renamed his band Afrika 70 which he later changed to Egypt 80.

Afrobeat as vehicle for Pan-Africanism

As success came, Fela’s lifestyle also changed. He became something of a cultural showpiece and a tourist attraction, pulling all progressive people around him and his house became a haven for Nigerian radicals, stirring people’s consciousness and awareness. His Afrobeat music became a vehicle for the ideological articulation of Pan-Africanism. Fela who saw himself first and foremost as an African, considered Black emancipation his endeavour. Afrobeat started to rule the airwaves. Contracts for international concerts started flowing in. Fela became a superstar!

Like many great artistes, Fela led two lives. He led a great creative and fulfilling artistic life on stage and a reckless and sometimes, violent one off stage. By the mid-1970s, he was at the peak of his creativity, prolific and genial. He churned out one record after another – Confusion, Lady, Shakara, Na poi, Yellow Fever, Eko Ile, Zombie etc. He was in his full glory as he galvanised crowds of thousands of Nigerian students with his words and with his very presence. He was mesmerising, artfully plaiting mordant humour with passion and uplift, defiance and courage and common sense; he was Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X, in one. Above all he was very Fela – very original. This was Fela at full strength – a man who could, in his own unique way, articulate the disorderliness of a land called Nigeria.

The eccentric in him

Emboldened by success, money, power and fame, Fela put on all the trappings of the superstar. Having declared his house “Kalakuta Republic”, a commune cum nightclub, he became a law unto himself and his eventual end was predictable. Touts and hangers-on in direct contradiction of the law publicly displayed marijuana around his premises. Strange things began to happen. The eccentric in him came to the fore as he began to wear underpants publicly and ran a commune of girls.

In 1977, in broad daylight, an estimated 1000 soldiers invaded “Kalakuta”, beating Fela unconscious, throwing down his 77-year-old mother from a two-storey floor (she died the following year of her injuries) and burning down the building. It was in retaliation for Fela’s record Zombie (1976) which satirises the life of soldiers and criticised military misrule.

Many members of the commune had to be hospitalised for various injuries. That singular event catapulted him to a bitter symbol of opposition to the Nigerian state. The following year, he married 27 girls, his dancers, in a controversial traditional ceremony.

In his club “The Shrine”, Fela was the chief priest and patriarch, his women, the sex objects and the touts became his subjects. Fela revelled in a sense of freedom that held him captive throughout his life. It compounded the paradox of the totally committed artiste, who escaping from the trammels of reality, becomes enthralled by the utopia of fantasy.

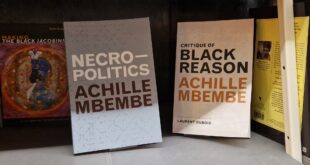

Fela’s songs and their message

That Fela through his music and his political philosophy questioned injustice, colonialism and racism, and advocated the emancipation of the Black race is a well-known fact. He was driven by a fanatical idealism for a beautiful society. His music, in his own word, was a “weapon” through which he sought to dismantle all cultures of hypocrisy, dishonesty and all forms of oppressive domination. He had a prodigious corpus of philosophy which encapsulated these ideals, and he sang about it in a language and tunes that are distinctively and inimitably his.

There is no gainsaying the fact that Fela might not have a rigorous, systematic ideology of an academic type, but in his chaotically fashioned message, his constituency – the underclass – understood and appreciated him. We cannot put his outputs down to a specific number, but he was a genius helplessly possessed by his ingenuity and as long as he lived, he never stopped to mobilise and inform the “wretched of the earth” with his songs. A catalogue of his evergreen songs testifies to this claim.

Lady for instance scorns African women’s efforts to assume Western identities and values, Yellow Fever condemns bleaching of the skin, Why Black men dey suffer makes Black consciousness, cultural pride and racial crusade its major concern. In fact, Afro-centricism was his classical theme. Other songs like Overtake-Don-Overtake-Overtake, Confusion Break Bone and Follow-Follow are the anti-establishment genres, which condemn misrule, oppression and injustice. Fela, in all these songs, x-rays the psychology of the oppressed and the poor. His Zombie, Army arrangement, Unknown Soldier, Sorrows, Tears and Blood, Soldier go Soldier come are Fela’s counter-attacks to personal humiliation and response to a repressive system and wanton abuse of the common man by the state.

Beast-of-No-Nation was a reaction to Botha’s “This uprising will bring out the beast in us”-declaration in the dying days of Apartheid and Teacher No Teach Me Nonsense satirises the inadequacies of Western political ideologies. Egbe ke Gbe (Bad Society) criticises the United Nations. Suffering and Smiling laments the mass gullibility of the masses and derided their pitiful lethargy and resignation.

Free from marijuana

With his Look and Laugh, Fela seemed to have been overwhelmed and exhausted by the hopelessness and futility of fighting for social justice and good governance in Nigeria and decided to just look.

And laugh he did. But he did not stop there; out of frustration, he did something else. He went through a pitiful moment of implosion and turned his fury against himself; he spurned all trappings of conventions and normality and finally found solace in all that is lewd and amoral until AIDS claimed his life.

It appeared that Fela, like lots of artistes, found it difficult to come to terms with the fact that he was just human, an ordinary human being. He really must have believed he could fly! Fela wanted to be free in his mind, so that he could compose and sing; he took to marijuana. He wanted to be free with his body and enjoy the virility endowed by nature, he got AIDS. Since his death, he has been truly free – free from marijuana, free from the law, free from all diseases. Since 1997, Fela has been really flying!

Nevertheless, we will always remember him as one of the unrepentant, committed fighters for the emancipation of the masses and the recognition of Black humanity.

Sun re o-Omo Abami Eda! (Rest in everlasting peace- the weird one!).

—————————

*Robert Ajani – scholar, journalist, communication consultant and media entrepreneur – lives in London.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.