Dessau is notorious for two brutal deaths of Africans in separate incidents — one of which occurred in police custody and remains unresolved. Even today, few of the city’s white residents see racism as a daily problem. Ben Knight reports

In the last 20 years, the eastern German city, where fewer than 4,000 of the 80,000 inhabitants are non-German, has been scarred by the two violent deaths of two African men.

The second of these, the case of a Sierra Leonean asylum-seeker Oury Jalloh, is the more famous, partly because of the still-unresolved nature of his death. In 2005, his charred body was found tied to a mattress in a police cell that had been engulfed in flames — campaigners are still convinced all the evidence points to a murder and a cover-up.

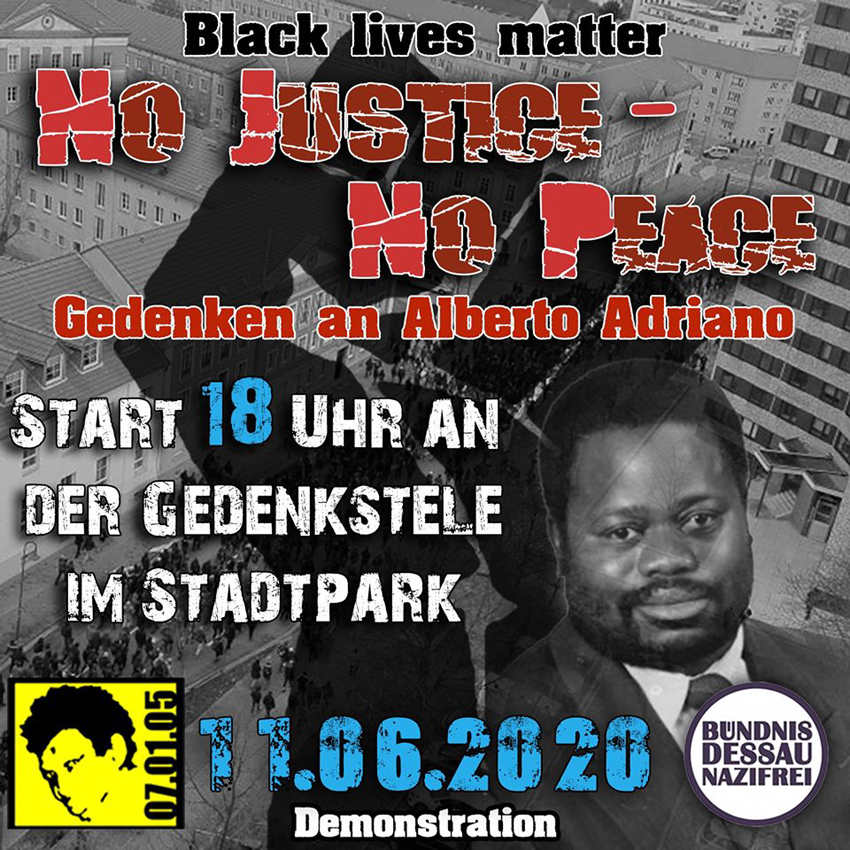

But there is no doubt about what happened to Alberto Adriano five years earlier. On the night of June 11, 2000, the 39-year-old Mozambican father of three was viciously beaten by three neo-Nazis just outside his home near the Stadtpark, Dessau’s historic city park.

He died three days later, in a coma, of massive head injuries. The three men who killed him confessed the same night, showed no remorse throughout the short trial, as contemporary press reports recorded, and were later convicted and sentenced — the eldest to life in prison, the others, who were both 16, to nine years.

Victim a ‘nice, friendly person’

Razak Minhel, director of Dessau’s multicultural centre, is still marked by grief as he sits in his office remembering Adriano. “He was a very quiet person, nice, friendly person,” he says. “Our children played together in that park — that playground that’s a crime scene now. That makes the memory very hard.”

Minhel joined the small commemoration in the city park on Thursday, along with a handful of local politicians, NGO representatives, and reporters. The annual event was a little better attended this year, partly because it marked the 20th anniversary, and partly because it comes in the middle of global anti-racism demonstrations triggered by the killing of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man killed in police custody in the US.

The ‘foreigners are rude too’

But noticeably absent from the commemoration were White Dessauers without an “official” reason to be there. Not that they do not remember why it is happening: All the passers-by DW spoke to recognised the names of both Adriano and Jalloh. “They still put all that theatre on?” one angry man sitting on a park bench said dismissively, before rambling fretfully about Germany’s economic future.

Others were clearly affected emotionally. One woman did not want to be interviewed, but as she walked off turned round and called out sadly, “It brings all those feelings back.”

Lutz, a tram driver on a break, said Jalloh’s case is still occasionally discussed at work: “He’s often talked up into some kind of folk hero, but it wasn’t like he was unknown: He sold drugs in the park, he harassed women,” Lutz alleged of Jalloh. Nevertheless, “of course something like this shouldn’t happen, and it should be investigated. It’s so awful for his family, his mother.”

“It’s a shame we do have a problem with the far-right in Germany, and you do notice it here in Dessau. Sometimes the foreigners are rude too, we should mention that,” said another woman who stopped to talk, but did not want to give her name. “But now that it’s happened in America too, also to a Black man, you do remember that it happened here too.” Not that she thought the deaths had given Dessau a bad reputation: “It was an isolated case,” she insisted.

For Minhel, Adriano’s death was a lot more than an isolated case — it was just the worst example of the many racist incidents he and people he knows experience every day: people verbally abusing and spitting at women wearing headscarves, authorities on the phone being rude and dismissive to people with a foreign accent, police even strip-searching Black people in public. Jalloh’s case, in particular, had fundamentally destroyed people’s faith in the police: “The police station is supposed to be the safest place in the city, isn’t it?”

The forgotten racism of communist East Germany

Adriano’s death also highlighted the hidden racism in the former East Germany (German Democratic Republic; GDR), which left deep divisions between German-born citizens and those newly arriving in the country. Adriano, who worked in a meat-processing plant, arrived in Dessau from Mozambique in 1988, among the last of East Germany’s Vertragsarbeiter, or “contract workers,” named after the bilateral migrant worker contracts the GDR signed with other socialist countries.

Under these contracts, thousands of people — mainly young men from Vietnam, Algeria, Angola, Mozambique, and Cuba — came to work in East Germany’s factories and coal mines, specifically to make up for a shortfall of labour. West Germany, which had a similar demand for cheap labour, brought in thousands of Turkish “guest workers.”

De facto segregation

In a 2016 article, historian Ann-Judith Rabenschlag described how the entire system was state-organised — the workers arrived in groups, and their contracts were organised for them. They also had very little choice in other matters: Where they lived and who they lived with was decided by the company that employed them.

READ ALSO: Remembering Theodor Michael, one year on

They were put in shared accommodation, with up to four people per room, with men and women strictly separated (even married couples could not get a room to themselves). Their stays were also supposed to be limited — residency permits automatically ran out with their work contracts, which were only granted for up to five years.

Though some effort was made to integrate the new arrivals at work (for instance through obligatory German lessons), Rabenschlag wrote that the segregated accommodation often led to tensions — to the extent that locals and migrant workers were sometimes actually moved further apart.

The Amadeu Antonio Foundation works to combat far-right extremism, racism and anti-Semitism. The foundation was named after an Angolan national who came as a contract worker to East Germany and was also murdered by neo-Nazis in 1990. According to the foundation, by 2000 when Adriano was killed, over one hundred people — more than ten people a year — had already been killed by far-right violence since German reunification. But Adriano’s murder sparked a nationwide reaction: Protests against far-right extremism were organised in Dessau, then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder arrived to pay his respects in person, money was raised for Adriano’s wife and three children, and the federal government funded new anti-Nazi education initiatives.

Hans Goldenbaum, director for violence and radicalisation prevention at Dessau’s multicultural centre, says all that barely changed anything. “It did bring an opportunity for civil society to fight for things that were needed, like mobile consultation centres,” he says. “Despite that, even though it was such a public case, after Schröder and all the others left, these people were left alone again. Asylum laws were tightened, far-right violence continued.” If anything, he added, the situation is even more threatening for asylum-seekers now because the far-right has become politically accepted — in the form of the anti-immigrant populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, which entered the federal parliament in 2017.

© DW

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.