The weeks-long standoff between Sea-Watch 3 and the Italian government ended with the arrest of Captain Carola Rackete, who has now been freed. But international maritime law and a country’s own laws often don’t chime, say experts.

Carola Rackete, captain of the search and rescue vessel Sea-Watch 3, was arrested on Saturday by Italian authorities for “resisting a warship” after her ship hit a customs and border police motorboat in the Mediterranean port of Lampedusa. Though there were no injuries, Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini described the incident as “an act of war.”

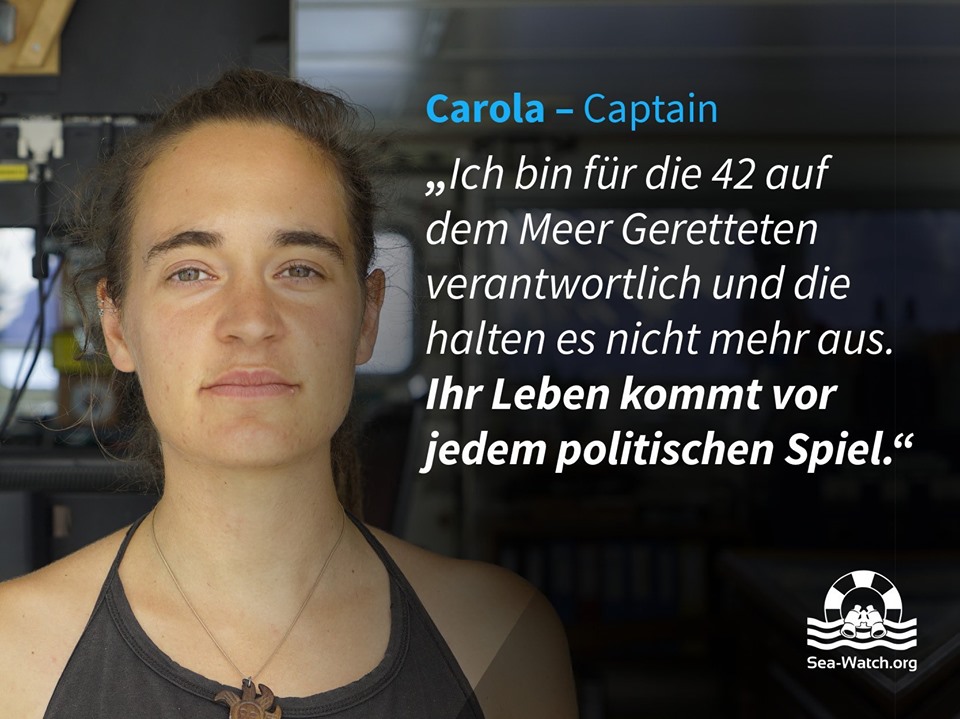

If convicted, Rackete could face 10 years in prison. She may also face a fine of up to €50,000 ($58,000), recently imposed by the Italian authorities, for bringing rescued people into its docks without permission. Sicilian prosecutors have also opened an investigation against Rackete for supporting human trafficking. A court on Tuesday has meanwhile freed her. [“I am responsible for the 42 rescued at sea and they can´t take it anymore, their lives are more important than any political game,” Rackete has repeatedly said.]

What international maritime laws did Sea-Watch 3 enforce?

Sea-Watch 3 says that Rackete, a 31-year-old German, was following international maritime law by rescuing and bringing them to a safe harbour. “There are certainly different areas of regulation that don’t really chime in with one another,” said Nele Matz-Lück, professor of international and maritime law at the University of Kiel. “On the one hand, there is the level of international maritime law, which says that captains must rescue people and bring them to a safe place, but there is no obligation for coastal states to be that safe place.”

For that reason, Salvini and the Italian coastguard were also within their rights to refuse entry to the ship and to use force to attempt to block the port. But, added Matz-Lück, it was of course “definitely not true” for Salvini to claim this constituted an “act of war.”

But it will be up to the Italian judiciary to decide how the incident between the boats is to be interpreted. In a statement released on Sunday, Sea-Watch said, “Captain Rackete performed all manoeuvres very slowly, in a non-confrontational manner so as to give the [Italian coastguard] boat plenty of time to get away from its position between the Sea-Watch 3 and the pier. … The two vessels only slightly touched each other.”

READ ALSO Italian court frees Sea-Watch captain

There is also room for interpretation over the condition on board. Though ships are normally obliged to follow instructions from a port, if the captain considered the situation on board an emergency (if food was running out and people getting sick), she would have the right to force entry into the port. “How bad the situation really is, is of course to a certain extent a question of interpretation,” said Constantin Hruschka, senior researcher at the Max Planck Institute for social law and social policy in Munich.

Could Rackete be prosecuted under human trafficking laws?

Under international law, trafficking “is only prosecutable when there is a profit motive,” said Hruschka. But that provision doesn’t exist in Italian law.

“That’s the big question now: Can a state decide that anyone who helps someone can be prosecuted,” said Hruschka. “EU laws say only that illegal immigration must be fought. And Salvini says it’s much more efficient if everyone can be punished, rather than making exceptions. So there is a certain interpretative space, which is why the case is boiling up so much.”

Why couldn’t the refugees be brought back to Libya?

Politicians from the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) were among critics who suggested that Rackete could have brought the refugees back to Libya, from where their stricken boat had set off (Lampedusa is closer to North Africa than mainland Italy).

“For one thing, there is no obligation to bring anyone to the nearest port,” said Matz-Lück. This rule ensures that trading ships, for instance, may continue on their intended route if they pick up people from stricken ships. “But it does have to be a safe place,” added Matz-Lück. “And a safe place doesn’t just mean dry land, it means a place where people can have their basic needs met. So Libya clearly didn’t qualify.”

Why couldn’t the migrants be brought to another European port?

During the 16-day standoff between Sea-Watch 3 and the Italian authorities, many argued that Rackete should have taken the ship to another European country. After all, Italian Foreign Minister Enzo Moavero Milanesi said on Friday that five EU countries had offered to take the 40 migrants: France, Germany, Finland, Luxembourg, and Portugal.

But, according to Matz-Lück, maritime law offers the captain in such circumstances a lot of interpretative room. “If she says the situation on board doesn’t suit that, or the water supply, or the fuel supply don’t suit it, then it’s up to the captain if the ship travels on or not,” she said. “There are no clear legal regulations of what should be done in such situations.”

Why can’t rescued migrants be distributed across Europe?

The European Union has no mechanism by which refugees rescued from the Mediterranean can be fairly and safely distributed across the bloc, which means, in effect, that there are likely to be more standoffs and crises like the one happening over Sea-Watch 3.

“If one could find a legal EU regulation agreed by everyone, they could be distributed,” said Hruschka. “But that’s always been the problem, that there have been countries who have voluntarily agreed to take in a few people. But there’s no mechanism.”

In other words, for each individual ship that arrives in Europe, the question is always asked anew: Who will take them? Italy and Malta have both said they will not let anyone on land unless other countries have agreed to take them in. “Why do they say that? Because if they land on their shores and make an asylum application and try to get protection, then the state would be responsible,” Hruschka said. This is stipulated by the Dublin system.

If other EU states said they would take the migrants, why wouldn’t Italy open its port?

This comes down to the hard-line stance taken by the Italian government. “Salvini’s idea is to close the ports altogether. He goes a step further; he says this is always trafficking, and so potentially criminal, and can’t be allowed,” said Hruschka. “The political agenda among the individual countries is very different.”

Author: Ben Knight / Copyright DW – All rights reserved

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.