BY STEFANIE HIRSBRUNNER / With Germany and Malta, yet another two European countries have recently approved gay marriage. While this is an important step forward in the struggle for equality, many LGBTQ people in other parts of the world still face severe discrimination [LGBTQ is an acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning. These terms are used to describe a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity]. One state that even prosecutes gay marriage is Nigeria. Two awarded authors, Elnathan John and Jude Dibia, met in Berlin to discuss the situation of LGBTQ in their home country. What is it like to write in exile, what difference can literature make and who has the right to tell stories with gay characters?

Elnathan John: I hate to be asked that question but let me ask it now anyway. What made you write the story The Way We Were?

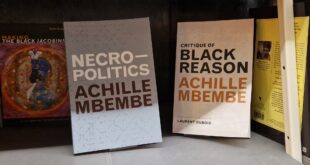

Jude Dibia: I left Nigeria in 2014 when our country came up with the law that supposedly was created to forbid same sex marriages. However, what it really was is an attack on the LGBTI community as a whole. And, what worried me was the fact that this law empowered and encouraged mob actions against LGBTI people. Between January and June 2014 when I left, all the stories I mentioned in ‘The Way We Were’ were stories that were coming up in the local papers: somebody being murdered in his bedroom; a student being hung; I even came across a video of two men being dragged into the street, stripped naked and forced to have sex with each other while people watched. All these things were happening systematically and so I thought I needed to record it, I needed to document my feelings in a short piece. Sadly I hardly ever read this story in public because I always get emotional. It reminds me of why I left; what is was like to live in Nigeria at that time.

Elnathan John: I remember when Walking with Shadows came out – a novel, which has a married man as the main character who is outed at some point at his work place. What was the Nigerian reaction to this?

Jude Dibia: I see now how successful the book became eventually, but it was hard to predict this. At first I could not find a publisher in Nigeria. Even the biggest ones, who all read the manuscript, came back and said “Fantastic story, but we cannot publish this because of the theme”. So eventually, when it was published copies were sent out to bookstores and libraries and again they all said they couldn’t stock this book. I understood because at the time when it came out just the word “gay” was already scary to even mention. Just to say that word was such a difficult thing. So what I did was to go for book festivals and readings and I would always take hundreds of books along with me. This book always created a sense of curiosity and in many ways started a critical conversation around the topic of being gay and Nigerian. People said the writer was brave to tackle such a subject. Of course, some people also thought it was gay erotica, which it is not. All these conversation created awareness for the book and it got to the point where people began ringing up my publisher and began asking for copies. It became my most popular novel.

Elnathan John: Do you find that there is a conflation of gay erotica with novels, which have either a gay theme or gay characters? Is there a sort of fascination, so when people hear “gay” they first think of erotica or sex?

Jude Dibia: Unfortunately, that is what a lot of straight people around the globe think when they think of gay people. They are so quick to jump to sexual conclusions when they hear the word LGBTI or gay. It is one of the things that make me disagree with people, gay or lesbian, who encourage the prefix ‘LGBTIQ’ when describing their profession. I frown at the term ‘gay writer’ or ‘gay author’ in describing me. You won’t go to a doctor or business manager and introduce them as ‘gay doctor’ or ‘gay business manager’ would you? And then the double standards and hypocrisy in Nigeria is ridiculous. Nigeria for instance has one of the highest consumptions rates of porn, especially gay porn. I think there is this idea that when you see a gay person automatically you think of sex. And while we do not label a doctor or a lawyer as gay or lesbian, I think that makes a lot of sense and we should also not do it with writers because we never see beyond that. We do not see an intellectual person who has feeling, we do not think of a family person who maybe has children or other responsibilities. The unnecessary sexualisation is something we cannot escape.

Elnathan John: The whole sexualisation leads to myths which people spread and you talk about this in your book. For example, those so called down-low men, the criminalisation of bi-sexuality because it is feared that these people spread HIV from the gay community and bring it into their straight relationships. How do you respond to the fear of glamorisation also, when we encourage people to come out, especially those who are married?

Jude Dibia: I would rather want to normalise the gay body, humanise LGBTIQ persons. People have attacked me and said my book is promoting homosexuality. I do not think it is doing that, it is more about clarifying what it is. I would like to see books where a character can go to see a doctor and on his desk is a picture of a man and two children and he will be asked, “Is this your family?”, and he will respond, “Yes, my husband is with the kids right now”. And no one will blink if that happens. As writers or opinion makers we have to invest in people´s perceptions. Less we forget, when Walking with Shadows came out people in Nigeria were saying gay people did not exist in Nigeria.

Elnathan John: I remember this famous cleric who said he had never seen a gay person in his life.

Jude Dibia: You begin to wonder, because we are so scared to show LGBTI people in our literature and in our film, it gives those people all the advantages to portray gays as something that they are not, for example as those who spread disease or paedophiles for example. Every time I see a gay person being mentioned in African media it’s almost always in relation to being a paedophile. And that gets to a point where even the unsuspecting people begin to buy into that false and misleading narrative. They soon begin to fear that their children could be violated by ‘gay’ people.

Elnathan John: We were just talking about why we write, how we write and who we write about. Also, what it feels like to write about something that you are not. We will move on to one of your other novels which is called Unbridled. In there you have a female character, Ngozi and Lauri Kubuitsile, the writer from Botswana, used two phrases to describe your portrayal of her: the “authenticity of Ngozi’s female voice coming from a male writer” and the “unique insight into the female psyche”. This brings me back to the question of how to write gay characters and whether or not other people can write gay characters. What would you like to see if someone who is not gay would write a gay character?

Jude Dibia: Look at the South African writer Zukiswa Wanner and her novel Men of the South for example which tackled the issue of gay relationships in Southern Africa. I think she has done an exceptionally good job. She is a straight woman, married with kids. When we get in touch with our humanity, everything is possible. It is like saying a man cannot be feminist. They may not be female but men can actually be feminists. I wrote about a woman in the first person narrative and that allowed me to get in touch with the voice, with this character itself and become this character, live in this character. It is actually very, very possible.

Elnathan John: Let me read a quote by Sunny Moraine: “If you are a straight cis woman writing MM romance, sorry, you are not striking a blow for equality. If you are in a position of privilege writing about people who are not, ask yourself if it is your story to tell. You may not arrive at an easy answer, you may not arrive at it at all but storytelling is fucking political.”

This raises the question whether or not male-male romance, mostly written by women, is not the fetishization of gay men and the exploitation of gay people for the pleasure of straight people. There is a market to the extent where some publishers, especially online publishers, reject any writing that portrays a body other than two male bodies in the story. And Jamie Fassenden kind of provides a reason for that when he says: “It seemed to me that male authors of gay novels were either depressed or obsessed with penis size. I want romance. And for that I turn to women.”

Jude Dibia: All writing is political. I do not agree with the fact that unless you are of a particular group you cannot write or represent that group. You for example wrote about almajiri and you are not one of them. However, you had enough contact with them to know how they think and feel. Basically, it was your humanity which made you tell that story. I think it is silly for anyone to say you have no right to tell that story because you are not one of them. What if one of them does not have a strong enough voice to tell the story and then there is someone, who can tell their story on their behalf? Part of the challenge of being a writer is to actually go out of our own comfort zone, explore and write about things.

Elnathan John: One problematic interview you had described you as being in exile. Do you see yourself as a person writing in exile or just a person who is not within the space he writes about?

Jude Dibia: I looked at the three books I have written in the last years and realized that most of my books where actually written when I was out of the country on holiday. It is so much easier to write when I am not within because then I do not have to deal with all the shackles of Nigeria. The power issues, the traffic is horrible, healthcare is non-existed – all these issues weigh so much on you that you cannot see through the fog. But when I am out of the country I can take a deep breath and look from outside into Nigeria more objectively. So it is easier for me to write from outside but I left the country on my own accord, which makes it a self-imposed exile. The tag exile-writer therefore does not bother me, I kind of made peace with that.

Elnathan John: A Nigerian book critic once stated that Nigerians are obsessed with the political and that we cannot simply write a beautiful story. He said we are busy trying to cloak politics in the garb of literature. What do you think of that?

Jude Dibia: The issue he was probably having is that most writers who are glorified or given a spotlight in the West are those who have written political stories or what some consider ‘poverty porn’ but I have seen all sorts of stories coming from the continent. I think we are not all writing political stories but rather human stories in a very sensitive era. If you write a love story in Nigeria, for example it is going to be difficult to escape the politics at the time when you are writing the story. Eventually you will always come back to that because we have not gotten to that space where everything is normal. In addition, I have read tons of fiction and non-fiction from Europe and America that mentions what is going on in the country politically as well, mentions the reality whether it is immigration or no jobs or healthcare issues or even war. These things influence all sorts of stories.

Elnathan John: Coming back once again to Walking with Shadows I would like to ask, do you find having a personal connection with the story — and I assume you do in this case — draws you closer to the characters you are writing?

Jude Dibia: I can totally detach myself from all my characters and still infuse myself with all of them. I like to write about uncomfortable things. For example, right now I am writing uncomfortable things about the reality of an artist who happens to be a migrant in Europe. You have to go to those dark places and remove yourself. I do not think anyone who reads my novels thinks “Oh this is Jude writing about himself.” If you do then you begin to have issues with the character. I always come up with some kind of character sketch, which I may not use in the end, but knowing he or she likes to drink coffee without sugar, the colour blue etc. helps to build that mental image of the person I want to write about. I might add some of my own characteristics to a number of different characters, my ideologies etc but that does not stop me from crafting unique individuals. I can totally shut myself out of the equation and simply write.

Elnathan John: There is a famous so-called Vlogger who did a whole video about “How to know if your man is gay” and she began by talking about those “Lagos boys” who according to her are all gay now. Then she listed five steps a woman should follow to find out about the sexuality of her husband. Those things are popular in Nigeria today. Why do you think that is?

Jude Dibia: There is this push for men at a certain age to be married. Even when you are gay and people expect you to be a man and get married. And while we still say gay people do not exist in Nigeria, others claim they can identify a gay person. Today we live in a global society though where men are very metrosexual. They are concerned about how they look, how they dress, they go to the gym, looking fit etc. So how can you say this is straight and this is gay? I have seen stereotypes turned over their head. There are effeminate men who are the straightest human beings I’ve met. And I met men who are very butch and very manly but they are gay and they embrace their gayness. So how can you claim to know who is what. In addition, my character Ada in Walking with Shadows has tons of questions after finding out about her husband: “How could I have missed the signs? Was it that I was blind?” I think not, because love is very fluid. I could easily fall in love with a woman the same way I could fall in love with a man. It is not one’s gender or what you have between your legs that defines who you are. It´s who you are as a person internally, which makes you attractive. At the end of the novel, my character also gets to understand that.

Elnathan John: What I liked about your main character Adrian is that you did not allow him to escape from his own part in all of this.

Jude Dibia: I found it important not to shy away from pointing out his responsibility. He understood and accepted his own flaws. There is a part in the book where the wife asks him: “You should have told me this because then I would have had a choice. Now this has happened and I had no say in it”. And he accepted that as well because he is not that innocent at all. His two gay friends Abdul and Femi also point out his flaws when they say he should not have married the woman regardless. So he carried that and I wanted to show that it´s not just a black and white thing where she is the good character and he is the bad one. The anger the woman feels at the beginning is how I would have felt as well, if I were in her shoes, we have a child together, and suddenly I find out, none of this is true. I wanted to show what happens when a society pushes people to act in a certain way to fulfil this ideal of what a man is or is not.

Elnathan John: And what made you do a revision of the novel?

Jude Dibia: In the original draft of the novel, there is a character, Rotimi, whose blind trust and faith in the main character Adrian is very interesting. At some point, he wants to show how much he supports Adrian and tries to kiss him to let him know it is O.K. but at the same time he keeps saying: “I am not gay, I am not gay”. In that sense he embodies the Nigerian man who believes that having sex with another man does not necessarily mean that he identifies as gay. It only means maybe letting off some heat. Therefore, I added some background to Rotimi’s character in the revision, some back history and how he treated another gay boy in high school. He is one of the most interesting characters in the book. People always remember Rotimi.

Elnathan John: I liked how you added layers to different characters who had different levels of exposure as far as sexuality is concerned. They all reach different levels of learning who they are and what their sexuality is. They all reach different levels of acceptance also.

Jude Dibia: I thought it was good that I listened to all sides of the story. I sat with many people who had strong opinions for or against homosexuality and what it meant to them. I remember how some parents think they can detect this in children and try to change that as well. In my book, we have a character that notices all of a sudden her son is playing with dolls instead of footballs and then she gets scared and she thinks, he might turn out to be like Adrian. Therefore, she strikes him. And when she has a conversation with her husband who is blind to that – ‘my son is not this, my son is not that’, he says. And when she talks to her friend who is Adrian´s wife and says I am scared my son might be gay, she is asked whether she would love him less. She does not miss a beat; she says no. But this is someone who has already shown a bit of homophobia towards Adrian and all of a sudden it is now her son and she says she would love him regardless. That also does something to Adrian’s wife because she begins to question why she is still angry with him in spite of all the explanation she has been given.

Elnathan John: There is something you also did in this chapter and it is to show how guilt by association can stop people from expressing their support for people who have a sexuality other than theirs. I see this even within the LGBT community.

Jude Dibia: Well it is not just you coming out. Everybody around you is being effected – your brothers, your friends, colleagues. Everybody who people know are close to you. In this age of social media with Instagram and all, anyone associated with you suddenly becomes suspect. Therefore, what I wanted to show is how one person´s story can affect multiple people around.

————————————-

Every quarter widely praised satirist, author of Born on a Tuesday (#BOAT) and Caine Prize finalist Elnathan John leads through an evening of literature. His novel “Born on a Tuesday” was published in German in August. In conversation with his guests from varied literary backgrounds and interests, he explores political and social questions of our times. Fiction, prose, poetry – join us for an astounding perspective on African literature. Next: Petina Gappah, 11th November 2017.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.