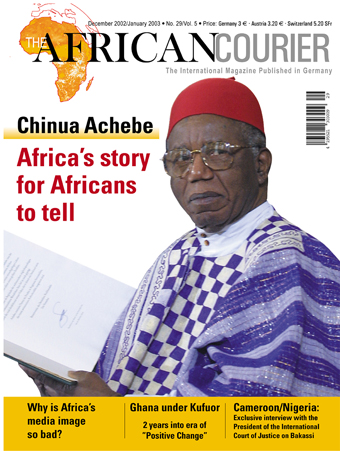

Africa’s literary giant Chinua Achebe died aged 82 on 21 March 2013. In celebration of the memory of the world-renowned Nigerian novelist, we republish here his speech in Frankfurt’s St Paul’s Church on 13 October 2002 after he received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. It’s one of his most important and enduring messages to Africans and the world.

—-

I was lucky to be born in propitious times, at a moment in history when it finally became possible for a young man in his twenties to ask difficult questions about his unsatisfactory condition in the world.

My people have made a proverb which warns inquisitive young men that a son who demands to be told what happened to his father before he has become old enough and strong enough to avenge him will end up suffering the same fate that his father suffered.

The strength I needed came partly from the accident of my location in time – at that point in our history when traditional Africa in retreat was yet present enough to leave a mark in the byways and shadows of our daily experience.

My other strength came from inquisitive reading. In time those savages I encountered in European “romances” about Africa by such authors as Rider Haggard and Joseph Conrad had to be accounted for. These weird characters, – ugly, barely recognisable as human, – were they fictional representatives of the people of my village, people I knew? The answer had to be no!

Where then would I go to encounter in fiction people like some of those I knew and sometimes even admired (as well as those I did not particularly like) in my village?

Read our books!

I decided to have a go at a fiction of my own for characters like the people I knew, neither writing them up nor writing them down. It seemed to me a simple matter of fairness that I should find them a home in my own story.

Three years ago [1999] the centenary of the birth of Ernest Hemingway was observed in Boston, Massachusetts. I was invited to take part in one of numerous panels on different aspects of his work.

Our panel was assigned the subject: Writing Africa and included, among others, Nadine Gordimer of South Africa and K. A. Appiah, Ghanaian scholar and critic.

The issue on which the panel seemed to be unanimous was Hemingway’s neglect of Africans in his cast of characters. Appiah drew attention to the episode in the famous story “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” in which Hemingway devotes considerable space and attention to the mind of a wounded and vengeful lion in sharp contrast to his depiction of the shadowy Africans who carry the guns and fetch the whisky.

At question time a member of the audience, in a noticeable combative tone asked how we on the panel would write Africa. I said to her with a little irritation of my own: Read our books!

If I had to deal with that encounter all over again, I would handle it differently. I would tell the young woman that in my fiction Africans are not banished to the margins of narrative or subsumed in landscape. Rather they become the movers of our story. Their humanity is not negotiable, it is not in the storyteller’s gift to bestow, to withhold or to grant grudgingly.

When the great Albert Schweitzer declared that the African was indeed his brother but only his junior brother, he spoke outrageous blasphemy, albeit a blasphemy that went unrecognized as such because of its long history and wide prevalence.

I would tell the young woman that I do not people my fiction with Africans lacking the power of speech altogether or speaking a half-baked dialect of English. The people I write about are often great masters of their own language and I have had to find an English equivalent that conveys the dignity, the gravitas of the original language.

If the young woman was still listening, I would direct her to my rendering of a family meeting in “Things Fall Apart”. The hero of the novel, Okonkwo, a proud and turbulent man, exiled from his community is given sanctuary by his mother’s people. But he is not consoled; his spirit is broken.

His old uncle, worried about him, calls a family meeting to address his despair:

>> “On the second day Uchendu called together his sons and daughters and his nephew, Okonkwo. The men brought their goatskin mats, with which they sat on the floor, and the women sat on a sisal mat spread on a raised bank of earth.

Uchendu pulled gently at this grey beard and gnashed his teeth. Then he began to speak, quietly and deliberately, picking his words with great care: ‘It is Okonkwo that I primarily wish to speak to’, he began. ‘But I want all of you to note what I am going to say. I am an old man and you are all children. I know more about the world than any of you. If there is any one among you, who thinks, he knows more, let him speak up.’ He paused, but no one spoke.

‘Why is Okonkwo with us today? This is not his clan. We are only his mother’s kinsmen. He does not belong here. He is an exile, condemned for seven years to live in a strange land. And so he is bowed with grief. But there is just one question I would like to ask him. Can you tell me, Okonkwo, why it is that one of the commonest names we give our children is Nneka, or Mother is Supreme? We all know that a man is the head of the family and his wives do his bidding.

A child belongs to its father and his family and not to its mother and her family. A man belongs to his fatherland and not to his motherland.

And yet we say Nneka – Mother is Supreme.

Why is that?’

There was silence. ‘I want Okonkwo to answer me’, said Uchendu.

‘I do not know the answer,’ Okonkwo replied. ‘You do not know the answer? So you see that you are a child. You have many wives and many children – more children than I have. You are a great man in your clan. But you are still a child, my child. Listen to me and I shall tell you.

But there is one more question I shall ask you. Why is it, that when a woman dies, she is taken home to be buried with her own kinsmen? She is not buried with her husband’s kinsmen. Why is that? Your mother was brought home to me and buried with my people. Why was that?’

Okonkwo shook his head.

‘He does not know that either’, said Uchendu, ‘and yet he is full of sorrow because he has come to live in his motherland for a few years.’ He laughed a mirthless laughter, and turned to his sons and daughters. ‘What about you? Can you answer my question?’

They all shook their heads.

‘Then listen to me’, he said and cleared his throat. ‘It’s true, that a child belongs to its father. But when a father beats his child, it seeks sympathy in its mother’s hut. A man belongs to his fatherland, when things are good and life is sweet. But when there is sorrow and bitterness, he finds refuge in his motherland. Your mother is there to protect you. She is buried there. And that is why we say, that mother is supreme. Is it right, that you, Okonkwo, should bring to your mother a heavy face and refuse to be comforted?

Be careful or you may displease the dead. Your duty is to comfort your wives and children and take them back to your fatherland after seven years. But if you allow sorrow to weigh you down and kill you, they will all die in exile.’

He paused for a long while. ‘These are now your kinsmen.’ He waved at his sons and daughters. ‘You think you are the greatest sufferer in the world? Do you know that men are sometimes banished for life? Do you know that men sometimes lose all their yams and even their children? I had six wives once. I have none now except, that young girl, who knows not her right from her left.

Do you know how many children I have buried – children I begot in my youth and strength? Twenty-two. I did not hang myself, and I am still alive. If you think, you are the greatest sufferer in the world, ask my daughter, Akueni, how many twins she has borne and thrown away. Have you not heard the song, they sing, when a woman dies?’

‘For whom is it well, for whom is it well? There is no one for whom it is well.’

I have no more to say to you.”<<

The Africa I write about is not inhabited by people without speech. I grew up hearing sometimes magnificent, and always efficient, language in my community. I did not hear the grunts and the screeches that savages were supposed to use in place of speech. So, I wrote what I did hear, in a translation that accorded equal respect to the two languages I have.

In the last lines of “Things Fall Apart” the white District Commissioner, who has just seen the body of Okonkwo hanging from a tree is thinking of the paragraph he will devote to this wild, turbulent savage in the book he planned to write. He is totally unaware, that Africa has moved in and taken back the right to tell Okonkwo’s story, and in so doing sent the Commissioner himself down to the footnotes.

** Extract of speech delivered by Chinua Achebe in Frankfurt’s St Paul’s Church on 13 October 2002 after he received the Peace Prize of the Association of Publishers and Booksellers of Germany.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.