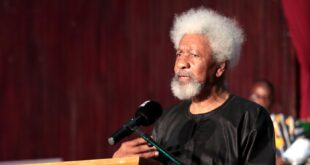

At the heart of Wole Soyinka’s whole corpus of work is man, mankind with all his intelligence and stupidity, writes Atim Ani*. The Nobel laureate pictures man, an African, in his constant struggle of adjustment to his changing environment, she posits in this essay on the significance of Soyinka’s body of work.

Wole Soyinka won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986. He is the first African winner in the Prize’s history. When he heard the news, he said: “This prize is recognition of our culture and our traditions in Africa, and I am very glad about it.” Although it is the very Africa that Soyinka seeks to criticise in his work, Africa being where his stories are set and where Soyinka proceeds with his study of mankind, he gives the same continent a powerful voice. An African perspective on world matters, society and the human condition in general is achieved in its richness and subjectivity. Africa is itself, and thus unmistakably, at its best.

There is no need for a philosophical approach to possibly understand or even define the African experience. Or, as the African-American literary critic Henry Louis Gates put it, “Soyinka is one of the few Black authors who assumes his propositions rather than claims them. This simple rhetorical gesture is devastatingly effective.”

Thus African-ness is confidently portrayed as given and the reader or audience, not being familiar with African reality, that is, the Nigerian specifically, is asked to make the necessary amendments in his/her perception. “No African writer has been more successful in making the rest of the world see humanity through African eyes,” as Eldred D. Jones beautifully summarises the significance of Soyinka’s work.

At the heart of Soyinka’s whole corpus of work is man, mankind with all his intelligence and stupidity. Man, an African, is pictured in his constant struggle of adjustment to his changing environment. Throughout his entire work Soyinka rejects false solutions to this struggle. Hence, man is caught in his self-constructed web of double-standards, false morals, unreal values and self-deception.

The Interpreters, Soyinka’s first novel, elaborately covers most of the themes that appear in Soyinka’s body of work. The novel is about a group of young Nigerian intellectuals trying to make something worthwhile out of their lives in a society where corruption prevails, yet social climbing and conforming matter.

Using his ‘technique of demolition’, Soyinka shows layer by layer that the values of the pillars of society are unreal and merely serve to conceal a rotten structure. Not only is society’s brittle scaffolding is torn down, but also the interpreters themselves face trials on a personal level that uncover less flattering conditions.

They, too, are “stripped naked” and forced to take off the mask erroneously worn to cope and succeed in a corrupt society, be the mask camouflaging escapism or the individuals’ lacking sense of direction. For, very clearly, the interpreters realise the problems and ills of their environment without being able to work at them effectively.

Unlike other members of society, they have access to power, if taken upon, and thus are in the immediate position of belonging to the very elite, the establishment, they so strongly reject and subsequently are able to change Nigerian society. “If you seek to transform, you must not be afraid of power” (The Interpreters).

All characters in the novel are eventually brought to judgement willingly or by force to honestly face their true humanness in its entire fallibility. Thus Soyinka, using a Nigerian setting, has portrayed a universal problem. This is what makes both the novel and the whole body of Soyinka’s work universally valid. Through the particular and the local, he sees through to basic universal human problems.

The Interpreters is a first novel, yet a literary masterpiece nonetheless. It is, in fact, “the first African novel that has a texture of real complexity and depth” (Gerald Moore), resulting from a period of intense literary work.

Wole Soyinka was no new writer at that point, so to speak. He moved into the novel form with authority, having meticulously explored the territory of drama, poetry and prose in a significant number of short stories, a number of remarkable plays and a corpus of distinguished poems.

In 1965, the year of the novel’s publication, there was also the first production of The Road at the Commonwealth Arts Festival in London, and of two radio plays, Camwood on the Leaves and The Detainee, by the BBC. By that year, The Strong Breed, The Swamp Dwellers, Brother Jero, The Lion and the Jewel and A Dance of Forests had all made appearances.

Soyinka successfully made use of the African experience and gave it meaning in art. He has made the fullest use of Yoruba mythology, the local pantheon of deities, the shrines, Nigerian landscape – the animals, the plants, the rocks, as well as power stations and night clubs. As early as in The Lion and the Jewel, he was employing Nigerian song, dance and mime, the use of which he perfected in the later A Dance of the Forests and Kongi’s Harvest.

The writer manages to integrate Nigerian forms into both plays in a homogenous manner that reflects a maturing in technique. In Idanre too, the mythology is not just added on, the mythology is the poem. All the ideas which appeared so early in his work reappear in more mature forms, and are presented with even greater technical skill in the later works.

Although primarily committed to Africa and Nigeria, Soyinka has lived on a large map since the 1960s. His plays have been widely performed, sometimes under his direction, and his novels and poems have been translated into many languages. His book of prison notes, The Man Died, and his autobiography, Ake, have been particularly admired abroad.

Whereas Ake, The Childhood Years, precisely documents Soyinka’s childhood, The Man Died records his arrest and interrogation, the efforts made to incriminate him and the searing mental effects of solitary confinement. The writer was imprisoned without trial by the federal authorities at the start of the Nigerian civil war in 1967. Ake contains an abundance of family details and crucial experiences that may give clues to the development of a complex personality.

Although he is a many-sided creative personality who expresses himself in various forms, Soyinka’s reputation is primarily that of a dramatist. His achievements as a playwright are certainly remarkable. The Lion and the Jewel, in which both media attention and marriage are significant themes, contribute in an amusing manner to the debate about the direction Africa should take as more and more nations achieved a degree of independence.

The Trials of Brother Jero developed a narrative-theatrical style to create a farce. A Dance of the Forests dared to draw dialogue drama and festival theatre together. The Strong Breed drew masterfully on Nigerian purification rituals and in the plays of the mid-1960s, Kongi’s Harvest and The Road, Soyinka is present as an assured playwright in control of different traditions: exploring the frontiers of drama, bringing together metaphysics and satire and combining festival theatre with the traditional drama.

While away from Nigeria during the early 1970s, Soyinka wrote Jero’s Metamorphosis and Death and the King’s Horseman, the latter containing some of his most powerful dramatic verse and representing the artist’s coming to terms with the theme of responsibility. That is, his own creative responsibility as an artist, and possibly giving evidence to the roots of his creative consciousness. The play carries the full weight of Soyinka’s ideas, indicated by the fact that he has returned to it repeatedly.

Soyinka’s work has always illustrated a concern with African politics, with African heads of state, with corruption in Nigeria and with American values. However, the plays of the mid-1970s and 1980s show a determination to comment directly and forcefully on Nigerian politics. This may also be attributed to the fact that in order to fully appreciate Opera Wonyosi and the satirical elements in A Play of Giants, the audience needs to be “an insider”, that is, to be well-informed about a considerable number of Nigerian scandals and familiar with the reputation of African heads of state.

At this point, I wish to expand on the idea presented at the beginning of my essay. For it is yet again this familiarity as an “insider” that enables Soyinka’s work to have such an outstanding African voice, proving to be important to the whole African Diaspora.

Soyinka masters African language rituals, implements them in his work and, in doing so, ultimately preserves an African tradition. These rituals are passed on from one generation to the next in a written and oral form of art. It is vital information, preserving language and culture. These are “our” texts, plays and songs.

In The Signifying Monkey, Gates explores the relationship between the African and the African-American vernacular traditions and Black literature, elaborating a new critical approach located within this tradition that allows the Black voice to speak for itself. Needless to say, Soyinka, being ahead of his time, had already matured literally with his Black voice by then. A maturity expressed not only in art form but, as a literary critic himself in various essays, on literature and culture. He addresses issues that demonstrate the undeniable importance of African criticism today.

African literature cannot be considered as the work of ‘primitive’ writers evolving into ‘civilised’ ones: that is the underlying argument of Professor Soyinka’s analysis on how the African world perceives itself as a cultural entity, and the differences between its essential unity of experience and literary form and Western literature.

Henry Louis Gates manages to identify Soyinka’s true role and significance in the Afro-related world and, in conclusion, argues that his work of literature and criticism “provide the African model to be strived for”.

Indeed, Soyinka is a key figure in the arts, and I hope to have given, no matter how briefly, an insight into the artist’s complex body of work. Soyinka’s “total theatre”.

Atim Ani has an MA in English and American literary and cultural studies. Born to Nigerian and German parents and raised in Nigeria, Jamaica and Germany, Ms Ani lives in Berlin

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.