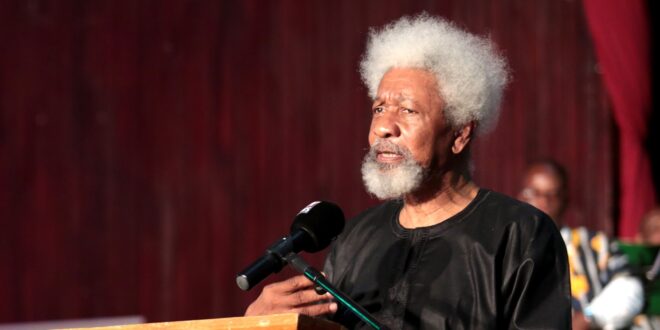

Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka turns 90 on 13 July. Femi Awoniyi and Michael Nnaji look at the life of the literary giant as a political and rights activist in the service of humanity.

Born Oluwole Akinwande Soyinka on 13 July 1934 in Abeokuta, south-western Nigeria, this truly great man of many parts is often wrongly reduced to the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he won in 1986, the first African to do so. But the playwright, actor, director, poet, novelist, teacher, raconteur and humanist is also a political activist of great importance.

Soyinka has, over the years, acquired in his home country the status of the conscience of the nation. He has played an active role in Nigeria’s political history since its independence from Britain.

In Soyinka, the artist is a politician who sees his work as an instrument for creating the society he considers ideal. In fact, political emotions run through its work. The life of the author shows that he even goes beyond the realm of his work to directly intervene in public discourse, seemingly not content with allowing his work alone to speak for him.

Soyinka was exposed very early in life to political influences. His aunt, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (the mother of the famous Fela Anikulapo-Kuti), led a women’s revolt over excessive taxation. That struggle led to the abdication of the Egba king, Oba Ademola II, in 1949. Ransome-Kuti’s political activism led to her to be considered as the doyen of women rights in Nigeria.

Soyinka’s own mother, Grace Eniola Soyinka, was also a member of that movement. She, as observed by the American-American scholar James Gibbs, was “a major influence on the young Soyinka. An energetic and extrovert woman of great presence and many accomplishments; she was a teacher, performer, political activist and trader.”

Soyinka’s own activism started in the early 1950s as a student of the then University College Ibadan, where he led the revolt against the tradition of “ties, gowns and so on” imported from Oxford and Cambridge, which demanded hall dining to be done strictly in the English tradition. Soyinka correctly identified these “ties, gowns and so on” as symbolic paraphernalia of an empty education system that was only meant train “a higher cadre of colonial stooges, administrators and intermediaries who would constitute the mandarinate to preserve and promote White interests” (Femi Osofisan).

While Soyinka was critical of the colonialist, he also expressed his misgivings about African leaders from early on. He was in London as a student in the late 1950s where he observed the rush of the African nationalists to their native lands anxious to grab the positions that would be vacated by the departing colonialists.

Soyinka’s misgivings about such a rush without deliberate plans or well-articulated programmes on what the Africans will do with the powers and responsibilities being handed over to them motivated him to write A Dance of the Forests, in which he presciently predicted the chaos and corruption of post-independent Africa. The play was presented at the Nigerian independence celebrations in 1960.

Soyinka has for more than five decades been mobilising public opinion and opposing the powers-that-be whenever he felt that some sort of line had been crossed. “From his classical liberal perspective, threats from the state to liberty of the individual and freedom of the nation are to be resisted with articulate, co-ordinated and self-consciously progressive forces,” wrote Tunde Adeniran, the Nigerian political scientist and politician.

Soyinka’s first brush with the post-independent Nigerian authorities came in 1965 when he was arrested for holding up a radio station at gunpoint and stopping the broadcasting of rigged election results. He was released after a few months of confinement, as a result of protests by the international community of writers.

Soyinka would later secretly and illegally meet the secessionist Biafra leader, General Emeka Ojukwu, in August 1967 at the risk of his life in an attempt to avert the Nigerian civil war. He was detained for two years in solitary confinement during the fratricidal war, which raged between 1967 and 1970 and caused the loss of millions of lives, for opposing the behaviour of the federal government of General Yakubu Gowon accused of waging a war of genocide against the Igbos.

“The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny,” he wrote in his powerful autobiographical work The Man Died, a collection of notes from prison, which was published in 1971.

After the war, Soyinka’s political activities were characterised by opposition to various Nigerian, but also other African governments (Apartheid South Africa and Idi Amin’s Uganda readily come to mind) by way of mobilising public opinion against them.

Matters came to a head during the regime of General Sani Abacha (1993-98). The Nobel laureate’s life was manifestly in danger, as the despot sought to silence all opposing voices. Soyinka was forced into exile from where he and his comrades-in-justice would continue their fearless opposition to the brutal dictator.

Soyinka has been a veritable scourge of dictators, and his antagonism towards religious bigotry and fundamentalism is no less compromising. He himself is an avid follower of the indigenous Yoruba religion, adopting Ogun, the deity of creativity, as his personal Muse.

Even as he ages on gracefully, Soyinka is still involved in activism although he has spoken of the need for the younger generations to step up to the plate and take up the baton.

This distinguished of all scholars still divides his time between universities in Nigeria and abroad in a remarkable show of academism where labour intersects with love. This man of diverse parts just keeps soldiering on. One can only wish this great African many more healthy and productive years to come!

Michael Nnaji is a medical doctor at the Charité University of Berlin and Femi Awoniyi is the editor-in-chief of The African Courier

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.

THE AFRICAN COURIER. Reporting Africa and its Diaspora! The African Courier is an international magazine published in Germany to report on Africa and the Diaspora African experience. The first issue of the bimonthly magazine appeared on the newsstands on 15 February 1998. The African Courier is a communication forum for European-African political, economic and cultural exchanges, and a voice for Africa in Europe.